Anti-spoiler and anti-trigger warnings: I will not be spoiling any narrative content of the source material, simply because “American Psycho” the novel and the film do not have anything to spoil. They are non-stories, plotless, and vibes-driven. I will also not be making any references to, quotations or descriptions of any specific graphic violent or sexual content.

Chapter One

As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to read “American Psycho” by Bret Easton Ellis.

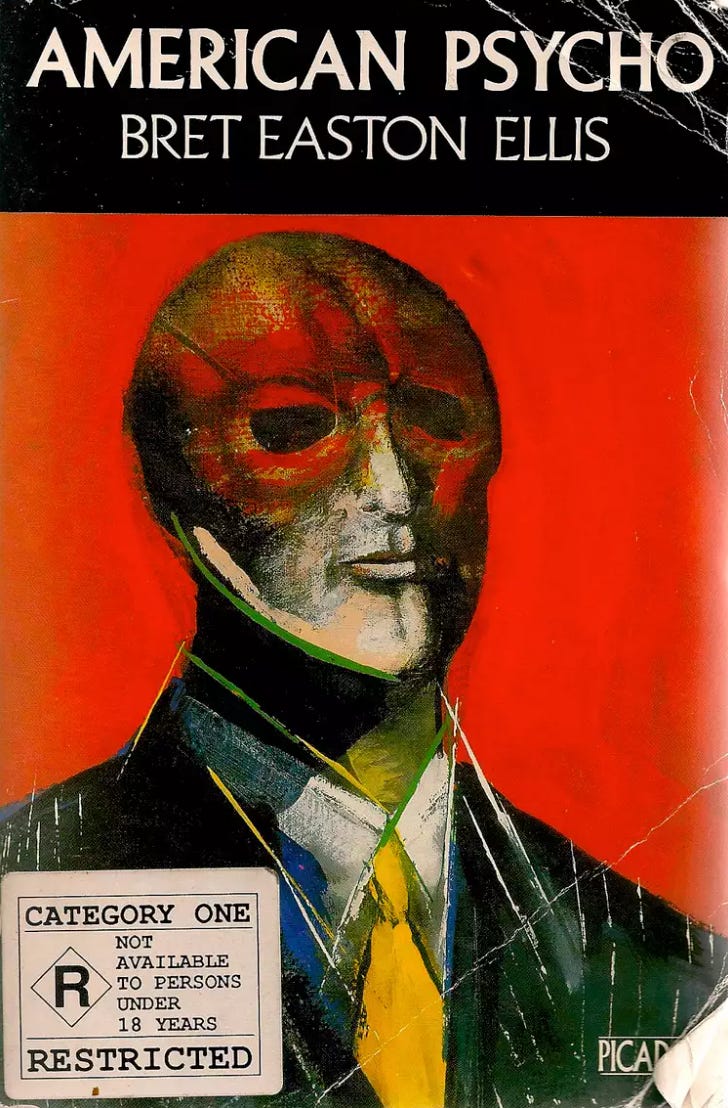

Back when bookstores still existed, I followed my dad into countless ones and occasionally saw the shrink-wrapped Australian paperback edition with the warning: RESTRICTED. I was dumbfounded.

I wasn’t some naïve kid. I’d already picked through most of Stephen King’s coke-fuelled 1980s output: the rampant scenes of child abuse, the graphic depictions of gore and domestic violence, infanticide and underage sex orgies. I’d borrowed these books from the municipal library. What could be worse? What warranted shrink-wrap and an age restriction? It’s just a book! Words on a page. All this secrecy only increased my fascination with the forbidden totem.

At age nine I already had an adult reading comprehension and was consuming mostly airport fiction from the likes of Arthur Hailey, Michael Crichton and Alan Dean Foster. If I wasn’t allowed to watch a movie that was rated R, I read the novelisation if it existed. But a book that itself was off-limits was new to me. And I wanted it bad.

Most consumerist rights of passage for kids who become legal adults involve purchasing alcohol or cigarettes. Me? The day I turned eighteen, I turned up to a chain bookstore with ID ready to purchase “American Psycho”. I was still in high school and dressed in full uniform. The (I assume) weirded-out clerk even asked for my proof-of-age, further adding to my rite of passage. I proudly displayed it and walked out. This grammar-schooled kid had just enacted his fully legalised act of rebellion. I’d never been drunk or smoked a cigarette, but I felt like a bad-ass.

Much like a silly kid smoking his first cigarette, when trying to read “American Psycho” for the first time, I did nearly puke. In fact, I only got about 90 pages in before I felt such disgust and self-recusal that I actually threw the paperback into the household council rubbish bin. I was not ready. I understood the rhetorical thrust: this was satire, born of a conflicted hatred of and attraction to the mores of a certain strata of society during a specific cultural moment that the writer was experiencing.

But I didn’t have the stomach for it. I’d never attempted any transgressive fiction until this point. And there was a certain specificity and intimate knowledge of the violence it was describing that I’d never encountered. Bret Easton Ellis says that he wrote most of the novel, sans the violent parts, in one duration. Then he researched the depths of depravity: the Marquis de Sade, artefacts from Nazi experimentation on human subjects, serial killer confessions, the kinds of material most would rather avoid. After that he wrote the repulsive parts. According to interviews, this was not an experience he enjoyed. “Sure, I was depressed, and I cried a lot, but who cares?” he mentions in one article. His drive to depict a brutal society through extreme and obscene metaphorical carnage was, to him, essential.

Bret Easton Ellis today is an openly gay writer. His facetious persona and its relationship to his oeuvre have become less slippery since the publication of his most recent book, “The Shards”. After he published “American Psycho” to a maelstrom of backlash for its undeniably misogynistic content and his disingenuous denial of any conscious effort to offend, his stance has softened. It’s been made into a movie, which arguably holds a larger piece of the cultural zeitgeist than its source material. There are Patrick Bateman memes and meta-ironic stances on what was, and still remains, a desperate cri de cœur from a problematic but important 20th-Century writer.

Chapter Two

"Abandon all hope" - Durante degli Alighieri

When the shrink-wrapped copy of “American Psycho” arrived at my doorstep yesterday, I immediately regretted my decision. The last time I owned a copy of this book, it ended up in the council rubbish bin.

Let me be clear (Obama voice): I did not want to write this series. But I feel compelled. Ever since my coming-of-age as a teenage edgelord, this book has lodged itself in my psyche.

That’s a very pretentious way of saying I experienced something akin to trauma, an overused Gen-Y cliché, but legitimate in this case. So, this series is part therapy and part exorcism. Join me, won’t you? (I know, sounds like a real treat, doesn’t it. But forewarned is forearmed. Or something.)

Prose and style: Form meets function

To his credit, Bret Easton Ellis provides the same warning in the very first sentence of “American Psycho”:

ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE is scrawled in blood red lettering on the side of the Chemical Bank near the corner of Eleventh and First and is in print large enough to be seen from the backseat of the cab as it lurches forward in the traffic leaving Wall Street and just as Timothy Price notices the words a bus pulls up, the advertisement for Les Misérables on its side blocking his view, but Price who is with Pierce & Pierce and twenty-six doesn't seem to care because he tells the driver he will give him five dollars to turn up the radio, “Be My Baby” on WYNN, and the driver, black, not American, does so.

Ellis favours these run-on sentences. I find them technically well-considered, precise and propulsive. There are few wasted words. I consider Ellis a great prose stylist more than a great writer. I don’t think he’d disagree.

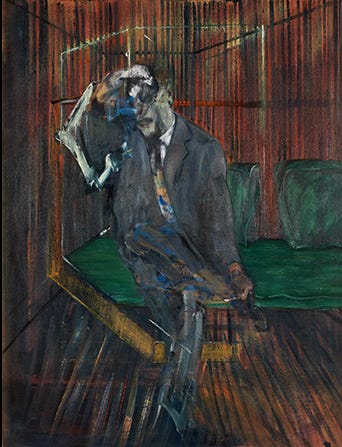

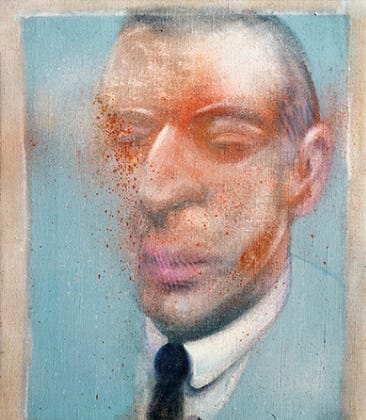

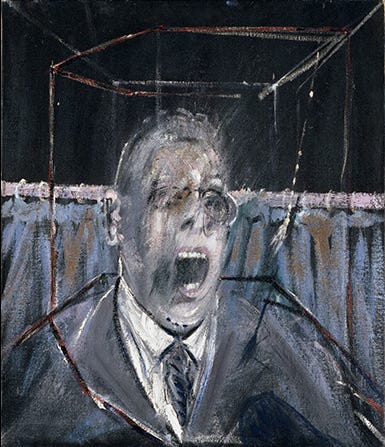

Ellis cites Joan Didion as a formative inspiration. In particular, the effect of the visual layout of her words on the page. Typeface, sentence length, line spacing: these things matter to him. Ellis measures the placement of words on a page, the negative spaces between paragraphs. “Painting with prose” might be over-egging the pudding, but the cover art on the first edition paperback of “American Psycho” strikes me as similar to some of Francis Bacon’s paintings.

And the effect of the prose does, too.

Study for Figure No. 4 (Oil on canvas, 152.4 cm × 116.8 cm (60 x 45.9in), Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide), c. 1954

Portrait of Jean-Pierre Moueix (Oil on canvas, Triptych: Each panel: 14 x 12 in. (35.5 x 30.5 cm), Private Collection, c. 1980

Study for a Portrait (aka Businessman I and Man's Head) (Oil on canvas, 66.1 cm × 56.1 cm, Tate Gallery, London, c. 1952

I say “the effect of the prose” and not the prose itself. Sentence-for-sentence, “American Psycho” is a chore to read. As a narrative, it’s stultifying. It’s intentionally repetitive and boring. But the effect of the prose has a mysterious quality.

A famous critic described the writing as “flat” and “pornographic” not in the sense of its content but its style. Over-lit, no detail spared, explicitly mechanical. That’s exactly accurate but there are surprises littered throughout. Moments of surreal within the mundane. An unusual reprieve from what is otherwise blunt-force sledgehammer black satire.

Ellis carefully considers both the first and last sentences of his novels as crucial elements. Starting your book warning the reader, via Dante’s Inferno no less, to abandon all hope is quite the opening gambit. Don’t expect an enjoyable experience, a moral lesson, a happy ending or even an ending at all. Buckle up, bucko. Caveat emptor. This is hell, and you’ve been warned.

The experience of reading “American Psycho” is more akin to watching a painting. Your eyes can dart around, you can skim, read non-sequentially, it doesn’t affect your overall experience. There’s no plot, no real forward momentum, it’s about vibes, baby.

Back to the cab ride:

“I’m resourceful,” Price is saying. “I’m creative, I’m young, unscrupulous, highly motivated, highly skilled. In essence what I’m saying is that society cannot afford to lose me. I’m an asset.” Price calms down, continues to stare out the cab’s dirty window, probably at the word FEAR sprayed in red graffiti on the side of a McDonald’s on Fourth and Seventh. “I mean the fact remains that no one gives a shit about their work, everybody hates their job, I hate my job, you’ve told me you hate yours. What do I do? Go back to Los Angeles? Not an alternative. I didn’t transfer from UCLA to Stanford to put up with this. I mean am I alone in thinking we’re not making enough money?”

You’re already getting a feel for the sledgehammer. Price is an asset, society cannot afford to lose him, and yet he doesn’t give a shit about his work and he deserves more money. Also, his last name is Price. And the firm’s name? Pierce & Pierce.

Sure, it’s funny, I guess. As far as “irony” goes for laughs. But beware the (inevitably white, male, second-year undergraduate) jackass who claims that the novel is “um, actually a really, really funny black comedy.” You’re thinking of the movie, not the novel, my dude. And you’re not impressing the female co-ed you’re trying to convince.

Funny or not, Ellis precisely captures cadence in dialogue. Notice the emphasis on “cannot” — he really has an ear for the way these people speak. He’s so good that I immediately want to punch this Timothy Price right in the face. What an entitled prick! Shut up, already! It’s enough to make someone… go insane?

There’s a lot to be said about the various script adaptations of the film American Psycho and its eventual production. We’ll get to that. But the fact that so much of the original dialogue remains in the 2000 film release is further testament to Ellis’ skill in capturing a certain voice.

Dangerous literature — and what I’m not going to discuss

Confession time: this Substack is called Double Takes and the intent is to write about films and TV series that I’ve seen more than once. But I haven’t read “American Psycho” more than once, at least, not cover-to-cover. Instead, I’ve dipped in and out, flicked through pages and read it non-sequentially.

This time, I intend to read it all the way through. With one caveat: for the sake of my own mental health, I will skim-read (or skip entirely) the discrete sections of violence that warrant that shrink-wrap packaging and the R18 rating. I’ve already read those portions during my edgelord teenage phase. I don’t need to stare back into that abyss. I will focus on how the film and the book align. The film cannot depict the abyss, because it’s essentially snuff film content.

If you’re not familiar with the source material, it’s basically this: Patrick Bateman is a young, wealthy and handsome Wall Street executive in the era of the go-go Reagan 1980s. He goes to a lot of expensive dinners, he works out a lot, and he kills a lot of people. (Almost exclusively, his victims are vulnerable and socially-marginalised women).

There’s a metatextual ambiguity as to whether Patrick Bateman’s carnage is real within the context of the actual story or if it’s contained within his own psychotic fantasy. He’s your classic unreliable narrator. There are paradoxes and contradictions that point to both interpretations. And Ellis is consistently slippery on the topic in interviews. This ambiguity has led to fanbase punditry every bit as tedious as the debate over whether Tony dies at the end of The Sopranos. It’s fiction, dummy: use your imagination.

The substantive difference is that the obscene carnage depicted in vivid, textural detail in “American Psycho” has an affective response on the reader. This is a book designed to hurt you. To say that these numerous, pages-long sequences of torture, sexual violence and cannibalism are shocking is insufficient. There are concepts and methods that no sane-thinking individual, even with the most morbid imagination, will have ever considered.

These passages are nigh-unendurable and your RPG character build will lose some sanity points. So readers who argue the case that the murders aren’t “real”, that they’re just “in Patrick’s imagination”, are less debating than pleading: even though this is fiction, tell me it ain’t so. I get it, buddy. But it’s already too late. You can’t unread a book.

Oh, and that final sentence? The one that links to the opening one?

Someone has already taken out a Minolta cellular phone and called for a car, and then, when I’m not really listening, watching instead someone who looks remarkably like Marcus Halberstam paying a check, someone asks, simply, not in relation to anything, “Why?” and though I’m very proud that I have cold blood and that I can keep my nerve and do what I’m supposed to do, I catch something, then realize it: Why? and automatically answering, out of the blue, for no reason, just opening my mouth, words coming out, summarizing for the idiots: “Well, though I know I should have done that instead of not doing it, I’m twenty-seven for Christ sakes and this is, uh, how life presents itself in a bar or in a club in New York, maybe anywhere, at the end of the century and how people, you know, me, behave, and this is what being Patrick means to me, I guess, so, well, yup, uh...” and this is followed by a sigh, then a slight shrug and another sigh, and above one of the doors covered by red velvet drapes in Harry’s is a sign and on the sign in letters that match the drapes’ color are the words THIS IS NOT AN EXIT.

From Dante to Sartre. Huis clos, baby! Hell is other people. This, I think, is kind of brilliant.

Chapter Three

"And as things fell apart / Nobody paid much attention" - Talking Heads

Okay (deep sigh): here we go, I guess? Part Three, baby!

Don’t worry, bud: it gets better.

Look, I’ll be honest. I still haven’t started re-reading “American Psycho” and I still haven’t gotten around to re-watching the movie. Now, wait: hear me out! Before you start hurling full wine bottles at your computer screen — let me explain.

This is an experiment. My previous exegesis of Goodfellas & Casino was a joy to write. There was a lot of meat on the bone, to use an expression that Patrick Bateman would appreciate. I felt it was somewhat successful in its aims: to express a fondness for both movies and to include my own takes on how they relate to craft, labour and capitalism.

I have no fondness for “American Psycho” the novel. As for the movie, I watched it once when I was 17-years-old and I don’t remember much about it.

I don’t believe either sources have much to say beyond the obvious. Rich people suck, particularly 1980s Wall Street rich people. Reaganomics left hundreds of thousands homeless after savage cuts to mental health care. Nobody cared, least of all the affluent who could afford to live in the Upper East Side. Terrible fashion trends and conspicuous consumption driven by unbridled deregulated financial markets produced a factory line of suspender-snapping, Oliver Peoples eyeglass-wearing, slicked-back-hair corporate dickheads.

You know, that guy!

Steve Castle, also known as That Guy (Source: Futurama, “Future Stock”, Ep. 53, aired March 31, 2002).

So my experiment with this series of posts is to write them “blind” based on semi-recalled knowledge and vague impressions. I don’t think it deserves more than that. For one thing, I didn’t sleep last night and I’m tired. But for another: have a look at the back cover of the 2022 paperback edition:

Bret Easton Ellis looks like a douche, we get the tired cliché of how “the American Dream becomes a nightmare” (thanks a bunch, F. Scott Fitzgerald, I’m still blaming you for that) and Irvine Welsh uses the word “exegesis” like an asshole. Who uses that word?

Sorry for that last part. Like I said, I didn’t sleep last night. Also my tummy hurts.

Surface, surface, surface

“American Psycho” the novel doesn’t have a plot per se, it’s a heavy-handed satire conducted via a character study told by an unreliable narrator. You all know that guy, right? Try to picture him.

Not that guy, the other one.

A brief Hollywood Insider tangent:

The American Psycho movie-version of Patrick Bateman has become a ubiquitous legacy meme and if you’ve been online in the past 100 years, you’ve probably already seen his face. There’s no doubt that Christian Bale’s performance is iconic: he is synonymous with Patrick Bateman, as far as popular culture is concerned. He did the work — starving himself, getting down to single-digit body fat, and then getting absolutely shredded.

There’s an anecdote that during casting, Bale turned up to a dinner with Bret Easton Ellis, already in character. Ellis was so perturbed that he asked Bale to knock it off. Method acting works — he got the role. By the way, did you know that Bale is Welsh? Either he’s a linguistic autodidact or his vocal coach deserves an Oscar.

Editor’s Correction:

Whatever, same same.

There are rumours that Tom Cruise was approached for the role but turned it down, despite being depicted as living in the same apartment building as Patrick Bateman in the novel.

I collect my mail — Polo catalog, American Express bill, June Playboy, invitation to an office party at a new club called Bedlam — then walk to the elevator, step in while inspecting the Ralph Lauren brochure and press the button for my floor and then the Close Door button, but someone gets in right before the doors shut and instinctively I turn to say hello. It’s the actor Tom Cruise, who lives in the penthouse, and as a courtesy, without asking him, I press the PH button and he nods thank you and keeps his eyes fixed on the numbers lighting up above the door in rapid succession. He is much shorter in person and he’s wearing the same pair of black Wayfarers I have on. He’s dressed in blue jeans, a white T-shirt, an Armani jacket.

To break the noticeably uncomfortable silence, I clear my throat and say, “I thought you were very fine in Bartender. I thought it was quite a good movie, and Top Gun too. I really thought that was good.”

He looks away from the numbers and then straight at me. “It was called Cocktail,” he says softly.

“Pardon?” I say, confused.

He clears his throat and says, “Cocktail. Not Bartender. The film was called Cocktail.”

A long pause follows; just the sound of cables moving the elevator up higher into the building competes with the silence, obvious and heavy between us.

Yeesh. When you creep out Tom Cruise, you must be a psychopath.

So anyway, Tom turned down the role, but many others were in the mix: Brad Pitt, with David Cronenberg directing. Leonardo DiCaprio, with Oliver Stone directing. Yeah, you heard me. Oliver freaking Stone writing and directing a movie called American Psycho. We almost got it, too. Proof that we’re not living the best of all possible timelines.

But who knows, maybe it would have been a disaster, like getting Verhoeven to direct when he already basically made American Psycho in Robocop. Still, I dream about the Stone version. Talk about mixing cocaine with cocaine. I used to have a copy of his script adaptation and I wish I could locate it again. It was bonkers. I remember a hallucinogenic sequence where splices of Wheel of Fortune were cut into Patrick’s internal descent into madness, each letter on the board slowly revealing a hideous truth.

Instead, we got the arguably safe choice: a feminist director to offset the misogyny; relatively bland, soap opera cinematography to suit the flat, sterile tone of the prose; and a hands-off approach to Ellis’ own screenplay adaptation.

Mary Harron, who had previously directed I Shot Andy Warhol, directed the film and co-wrote its screenplay with Guinevere Turner. This screenplay was selected over three others, including one by Ellis himself. Turner claims Ellis’ only complaint with the film was Bateman’s moonwalk before killing Paul Allen. In the novel, Patrick Bateman’s favorite artists are Genesis, Huey Lewis and the News, and Whitney Houston. An entire chapter is devoted to each.

Source: https://www.projectcasting.com/blog/news/american-psycho-movie-script

BTW: Bret, you’re a moron. The moonwalk ruled in that scene. And you got your Huey Lewis shimmy, so shut up!

Ask a stupid question, get a boring answer

But who is Patrick Bateman?

BATEMAN (V.O.)

My name is Patrick Bateman. I am twenty-six years old. I live in the American Garden Buildings on West Eighty-First Street, on the eleventh floor. I believe in taking care of myself, in a balanced diet, in a rigorous exercise routine. In the morning, if my face is a little puffy, I'll put on an ice pack while doing my stomach crunches. I can do a thousand now.

That’s Patrick Bateman. There’s nothing behind the surface. He is defined only by superficial qualities. They are meticulously, mind-numbingly described in the novel. I’ll spare you the four-page explanation of his beauty routine, because it’s torturous. But here’s a glimpse into the abyss:

And that’s just his skin and hair care routine. Don’t get me started on his workout regime or his wardrobe collection. The entire novel is like this: every character is introduced first by name, then couture.

Price seems nervous and edgy and I have no desire to ask him what’s wrong. He’s wearing a linen suit by Canali Milano, a cotton shirt by Ike Behar, a silk tie by Bill Blass and cap-toed leather lace-ups from Brooks Brothers. I’m wearing a lightweight linen suit with pleated trousers, a cotton shirt, a dotted silk tie, all by Valentino Couture, and perforated cap-toe leather shoes by Allen-Edmonds.

And look, I get it. I said in the previous post that reading the novel is like watching a painting. A very boring, abstract painting. Prose is style, content is vacuous. Yada yada, the effect of the prose is its own statement on the topic’s main thesis; it’s like, meta or something, dude.

The problem is that, for me, the canvas is too large. Three hundred and eighty-six pages is too long for this kind of painting. Particularly with such dense typeface and minimal line spacing in the typeset. No wonder Ellis had to punctuate the doldrum with numerous pages-long passages of mutilation, cannibalism and sexual violence. You might say it’s a contrast, like in a painting. But I think it’s largely to jolt the audience awake, stir controversy, gain notoriety and sell copies.

But, like, what are you really about, Patrick my dude? Rap with me here. Let’s grab a magnum of Finlandia vodka and bro-out. I’m ready to hear about the real you. (I’m just ribbing you: I know you’re a J&B rocks guy).

BATEMAN (V.O.)

There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there.

Woh, edgy, dude! That’s like… deep.

Already bored? Me, too. Let’s move on.

Vacant interiors

Surely Patrick has an inner life? Thoughts, hopes, desires? Oh right, I forgot: he’s That Guy. Abandon all hope, etc.

Everything failed to subdue me. Soon everything seemed dull: another sunrise, the lives of heroes, falling in love, war, the discoveries people made about each other. The only thing that didn’t bore me, obviously enough, was how much money Tim Price made, and yet in its obviousness it did. There wasn’t a clear, identifiable emotion within me, except for greed and, possibly, total disgust. I had all the characteristics of a human being — flesh, blood, skin, hair — but my depersonalization was so intense, had gone so deep, that the normal ability to feel compassion had been eradicated, the victim of a slow, purposeful erasure. I was simply imitating reality, a rough resemblance of a human being, with only a dim corner of my mind functioning.

Well, it was worth a shot. But I’m being mean (see: hurt tummy) when I should be more charitable. I think the movie, according to my dim recollection, was more successful than the novel. For one thing, it was actually funny.

To be fair, “Fore!” is a decent album but not as good as anything by Genesis.

Next post, I’ll zip this series up in a body bag and try to bring some joy and enthusiasm at the same time. Just like Patrick. If not for my sake and yours, at least to honour the legacy of all those Bateman memes and American Psycho’s problematic legacy for a certain type of young male.

Chapter Four: Full Joker Mode Activated

"Even if you're innocent / You can cause too much embarrassment" - Genesis

Time for a little night music. Don’t you love farce? Enough with the Sturm und Drang of the previous posts. There’s a danger in taking oneself too seriously: inevitably, you end up the fool. On with the show. Send in the clowns. Including myself…

There is humour to be found amongst the carnage of American Psycho the film, and I suppose, “American Psycho” the novel. (From what I remember: keep in mind, this series is an experiment. I haven’t re-watched the movie or re-read the book. I’m relying on faulty memories that are over 20-years-old.)

Patrick Bateman is somewhat clownish once you skip over, or skim-read, or choose to interpret his carnage as “imagined” within the diegesis of either text. The film largely obviates the explicit details of his murders, for obvious reasons. Sure, he’s a psychopath but he’s also kind of funny.

With that facial expression, this could be a screenshot from an SNL sketch.

The title is “American Psycho”, but as with clowns:

As Sondheim explained in a 1990 interview:

I get a lot of letters over the years asking what the title (ed: “Send In The Clowns”) means and what the song’s about; I never thought it would be in any way esoteric. I wanted to use theatrical imagery in the song, because she’s an actress, but it’s not supposed to be a circus [...]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Send_In_the_Clowns

Bret Easton Ellis is similarly idiosyncratic in his explication of the book when being interviewed. Let’s sidebar that because I learned in undergrad that the author is dead. Not literally; as far as I know, Bret is still posting Boomer-reactionary tweets while barred-out on Xanax and writing dud screenplays. I mean “dead” in the literary theory sense. And in the other sense that Marshall McLuhan meant, when he was writing about… look, whatever. Who cares.

Yak yak yak… get a job!

The point is, I’m not a postmodernist. I don’t get Theory, or even why it needs to have a capital ‘T’. Either because I’m stupid or because postmodernism is dumb. I choose to believe the latter. And postmodernism can’t prove me wrong because it’s built on shifting sands that allow me to construct my own terms. “American Psycho” is a postmodern text. So either it’s dumb, or I am. Or both? Academics, feel free to weigh in, you clowns. (That’s all I got out of my BA, other than $30,000 in fees and debt. Who’s laughing now?)

Basically postmodernism (see above and save yourself doing a BA).

One Last Stab In The Dark (or two)

I’m closing out this failed series with two final ideas. If you’ve read this far, I salute you. I’m also going to have to provide some kind of amendment to the trigger warnings. In order to sacrifice this calf, I will be referring to a specific scene in the movie that involves a man getting killed by an axe. Don’t worry, he deserved it. He paired the wrong Versace silk necktie with the wrong Valentino four-button blazer.

(Also, relax: if you’ve watched the scene in Casino where the Irish guy’s head gets squeezed in a vice until his eyeball pops out and his throat is slit, you’ve got nothing to worry about. You sicko.)

“Alright, y’know what? This one’s dumb. Dump it. Trash it. This one’s garbage.”

Patrick Bateman kills, maims and tortures a lot of people. Mostly sex workers and homeless people whose disappearances go unnoticed. Nobody cares or pays attention. He does, however, quickly dispatch a rival Wall Street colleague without any prolonged suffering. That victim is Paul Allen, who Patrick hates because he has a slightly nicer business card and an slightly more upscale duplex apartment.

I guess that’s funny if you think about it, but thinking about jokes kind of deadens the punchline. Also when you don’t think about it, it’s not really funny. Look, just watch the movie and don’t read the book. You’ll see why in a minute.

The central “tension” of the back half of the non-story is whether Patrick will be implicated in his murder of Paul Allen. A detective is assigned to the case of Allen’s mysterious disappearance because this victim is one of the Masters of the Universe: a hard-charging Wall Street executive, white, male and rich. The detective in the movie is played by the inimitable Willem Dafoe.

(Non-spoiler: it comes to nothing.)

Patrick gets away undetected, either because nobody would ever suspect someone like him to be a psychotic murderer or because all of the characters in the novel are interchangeable clones of That Guy who constantly get mistaken for one another. Even after a public murder spree where he rampages around Manhattan with a handgun like a bored GTA player, shooting pedestrians and inexplicably blowing up a car, there are no consequences. Towards the end, he calls his lawyer on the phone and leaves a message, confessing everything he can remember.

BATEMAN

Harold, it’s Bateman. Patrick Bateman. You’re my lawyer so I think you should know — I’ve killed a lot of people. Some escort girls, in an apartment uptown, some homeless people, maybe five or ten, an NYU girl I met in Central Park. I left her in a parking lot, behind some donut shop. I killed Bethany, my old girlfriend, with a nail gun. Last week I killed another girl with a chainsaw — I had to, she almost got away. There was someone else there, I can’t remember, maybe a model, I can’t remember but she’s dead too. And Paul Allen. I killed Paul Allen with an axe, in the face, his body is dissolving in a bathtub in Hell’s Kitchen. I don’t want to leave anything out here... I guess I’ve killed 20 people, maybe 40 — I have tapes of a lot of it. Some of the girls have seen the tapes, I even... well, I ate some of their brains and I tried to cook a little.

“Tonight I just, well, I had to kill a lot of people!”

The confession means nothing. Patrick hangs up the phone and the movie finishes with him going for drinks at Harry’s. I think, in the novel, the lawyer calls him back and compliments him for making such a funny joke.

Editor’s Note

I searched via CTRL+F after Googling “american psycho script” and found this dialogue below. I don’t know if it made it into the final movie, because I watched it when I was a teenager. Apparently in this script version, the lawyer is called Carnes.

(I guess Carnes as in carné, French for “meat-based” and “bone meal”. Or maybe as adjacent to carnival, as in clowns? Just speculating. I have only enough room in my brain for one language.)

BATEMAN (Desperate, shouting)

Wait. Stop. You don’t seem to understand. You’re not really comprehending any of this. I killed him. I did it, Carnes. I’m Patrick Bateman. I chopped Allen’s fucking head off. I tortured dozens of girls. The whole message I left on your machine was true.

CARNES

Excuse me. I really must be going.

BATEMAN

No! Listen, don’t you know who I am? I’m not Davis, I’m Patrick Bateman! I talk to you on the phone all the time! Don’t you recognize me? You’re my lawyer.

Carnes stares at him in confusion and annoyance.

BATEMAN

Now, Carnes, listen to me. Listen very, very carefully. I killed Paul Allen and I liked it. I can’t make myself any clearer.

CARNES

But that’s simply not possible. And I don’t find this funny anymore.

BATEMAN

It never was supposed to be!

Make of it what you will.

There’s no relief for Patrick: even when he seeks damnation, nobody will take him seriously. When a clown takes of his make-up, he’s still untrustworthy. He’s trapped in Hell. He doesn’t realise he was damned from the beginning.

If I’m being charitable, this is a pretty good modern adaptation of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, which Ellis cites before the start of the novel.

Is this… postmodernism?

Thanks to brain-rot from being terminally online, I’ve gradually equated “irony” with “humour”. That’s a problem. Patrick’s innocence in the eyes of society despite his desperate attempts at self-incrimination is ironic. But it’s not the funny kind of irony. It’s the kind that is satirical. You know, the annoying kind.

I don’t need to explain why Patrick is never taken seriously or why nobody believes that behind the clown mask there lies a monster. You get it, right? The real psychopaths are the friends we met along the way. Everybody in his social milieu is a psycho, whether they actually murdered people or not. They make a “killing” on the stock market and their passive profits don’t trickle down to anybody, their non-labour means nothing, Reagan was wrong: in fact, it probably led to higher homeless and mortality rates for the bottom strata of society. They’re killers, too, just in an acceptable way that society validates and rewards handsomely. They dress sharp, they’re cut-throat, they slash costs. OK, I already know you got it: sorry for using the sledgehammer to drive the point home.

It would cause too much embarrassment (Genesis song link alert) for the law establishment, or his peers, to accept that Patrick is actually a killer. It’s too on-the-nose. Much like the book.

Cutting it all together

In the novel, Paul Allen is killed while blathering on about something irrelevant with Bateman cutting him off midsentence via an axe to the face. He dies immediately. It’s probably the only “humane” murder in the book, which led to the outrage and the deserved interpretation of intended misogyny.

Somewhere else in the book there is an entire chapter devoted to a slavish critique of the entire discography of the band Genesis. It’s “funny” that Patrick likes the music of Whitney Houston, Huey Lewis and the News, and Phil Collins, because they’re arguably some of the most sterile, banal artists of a decade that produced much more captivating pop music.

The movie ingeniously integrates these two chapters in one scene.

Patrick kills Paul in his apartment after an impassioned diatribe explaining why Huey Lewis shouldn’t be compared to Elvis Costello, because “Huey has a more bitter, cynical sense of humour” (lol: irony). Paul is slumped in an armchair, sloshed on Scotch and he isn’t paying attention. But he should be paying attention because the floor is covered in newspaper for some reason, all the furniture is draped in protective canvas, and Patrick is dressed in an Armani raincoat while ranting like a lunatic. He’s also carrying around an axe and dancing like a clown.

That’s Jared Leto, pre-Joker.

This is the most mimetic scene in the film because Bale’s performance is so funny. He really captures the unhinged lunatic inside Bateman as well as his clownish side. His response to Allen asking if that’s a raincoat he’s wearing by ecstatically replying “Yes, it is!” is hilarious because of his line delivery.

His white-guy-dancing is funny, too.

And then, while Paul Allen isn’t paying attention, Bateman goes for the kill.

BATEMAN

I think I their undisputed masterpiece is “Hip To Be Square,” a song so catchy that most people probably don’t listen to the lyrics. But they should because it’s not just about the pleasures of conformity and the importance of trends. It’s also a personal statement about the band itself.

We follow BATEMAN from behind as he walks up to Owen, the axe raised over his head.

BATEMAN

Hey, Paul?

WHACK!

Patrick screaming, “Try getting a reservation at Dorsia now, you fucking stupid bastard!” to Allen’s corpse is actually funny to me.

This is the only scene from the film that I remember vividly. I guess irony can be funny, after all.

Shoulda listened to those lyrics, Paul.

Final thoughts

This is not an exit. I don’t have any final thoughts. Sorry for the troll. But maybe, if we’re being postmodern, this is meta-irony. So, like, not really funny and not very smart, either. I guess the joke’s on me: I decided to write this confession. And it took a lot of time, and sure, I cried a lot, but who cares? Nobody will notice.

Kind of funny, when you think about it.