Note: This post contains spoilers for Goodfellas (1990, dir. Martin Scorsese) and Casino (1995, dir. Martin Scorsese)

I first watched Casino when I was around fifteen-years-old. I watched it on a modestly-sized TV when it played on free-to-air on a Sunday night in my childhood home’s living room. It was 1998.

It was like nothing I’d ever seen. In my head, it was the first R-rated film I had watched. Turns out my memory is wrong: I’d seen Apocalypse Now, Taxi Driver and The Godfather. But this was something different. Casino was hands-down the most violent and gleefully amoral movie-watching experience of my life.

For a 15-year-old, that was enough to sear it into my brain. And it wasn’t just the content. I didn’t know what “cinematography” meant back then. I had never heard of movie-crafting terms like “whip pan”, “smash cut” or “rack focus”. But I knew something: Casino was fun. It was completely captivating. Despite the 2 hours 58 minute running time (plus at least one hour of commercial breaks) I was glued to the screen. It had glamour. It was depraved. It was completely seductive while also transgressive in a distinctly amoral way.

I’ve watched Casino too many times to count. At least over forty times, maybe more. On my first solo trip overseas, I found a VHS copy in Tokyo and watched it every night, during the third week of a trip to Japan that had started to get lonely and isolating. To me, it’s like Heat, it’s a movie that never gets old: I’m always entertained.

Over the years, I’ve encountered a lot of Casino detractors, who compare it unfavourably to Goodfellas, or who criticise its bloated runtime or its excessive use of expositional voiceover (there are over 400 lines of V.O. dialogue in Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese’s final script). I’ve come to terms with its formative place in my personal movie-watching history, and I’m aware that personal tastes my vary.

But I want to go to bat for Casino (kind of like how Nicky got the bat in the third act) and explain why I think it’s unfairly dismissed. While it’s not a masterpiece, I want to argue that comparing it to Goodfellas (as happened with reception to The Wolf Of Wall Street) is unfair. And that my initial read of the film as gleefully depraved and distinctly amoral was wrong. Casino is indeed a morality tale. Maybe not a cautionary one, but a fatalistic Christian one about greed and control, the garden of Eden and false paradise, human fallibility and how:

NICKY (V.O.)

in the end...

INT. TANGIERS SPORTSBOOK/ACE'S OFFICE - NIGHT

ACE looks over the casino he rules.

NICKY (V.O.)

...we fucked it all up.

For fans of any art form, a lot of the context for appreciation is autobiographical. Whether it’s the first time you heard “Pet Sounds” by The Beach Boys playing at a hipster house party and spent the rest of the week listening to it, or (if you’re lucky) being taught T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” by your favourite high school teacher and finding some resonance with your own teenage turmoil, age and sequence matters.

I watched Casino before I’d seen Goodfellas. Both are gangster flicks directed by Scorsese and based heavily on source material by Nicholas Pileggi. If you talk to most Gen Y film buffs, this matches their experience. But it’s the reverse chronology: as Gen X film buffs like to point out: Goodfellas came out first. And, to many of the latter camp, Casino is a derivative and inferior successor to the first.

Goodfellas v. Casino and the False Dichotomy

When you meet someone who likes the same movies as you, it’s a fun icebreaker question: “Goodfellas or Casino, whaddaya got?”

On paper, it seems like a fair comparison. Both movies have the same director and writers, similar source material, much of the same cast and familiar story beats. Joe Pesci’s unpredictable and violent Tommy DeVito in Goodfellas is basically Joe Pesci’s unpredictable and violent Nicky Santoro in Casino. Both movies allow you to share in Scorsese’s ambivalent attraction to and repulsion of the Mafia lifestyle. And they’re both excellent movie-watching spectacles with a large and ardent fanbase.

To the extent that arguments based on subjective matters of taste can be settled at all, the critical consensus tends to hand Goodfellas the blue ribbon on precedent alone: it was made first. Casino stands in its shadow, cast as a pale runner-up. But such a simple calculus in a zero-sum argument is inherently misguided. Sure, they share the same DNA. But it’s like asking a parent to choose a favourite child (OK, maybe don’t do that). Surface similarities aside, both movies dazzle from different aspects. And it is these aspects that I believe can disproportionately weigh the discussion.

First impressions last

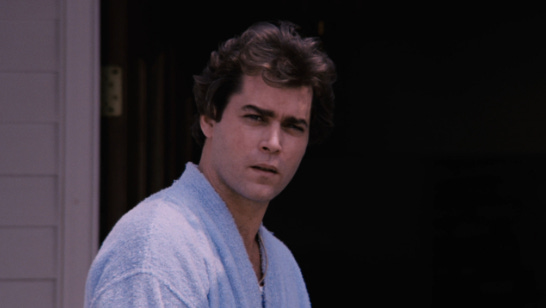

Goodfellas opens with a stark title credit sequence that whips past the screen, white text on black background, to the sound of whooshing traffic. It only gets halfway through before we cut to a dark highway. A car is in motion. We get our first look inside and the protagonist, Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) is driving.

Immediately, something alerts Henry and the car’s passengers that something’s up: there’s a sound like driving on a flat tire. We have no context for what’s going on. The movie starts in media res and the characters in the scene have only slightly more context than the audience.

When they pull the car over to the side of the highway, we’re quick to learn that extra piece of context. Henry and his pals are driving around with a body in the trunk. They thought their cargo was dead, wrapped in a blanket and ready for disposal, but it’s not. The car’s brake lights drape the scene in an ominous red. Henry opens the car’s trunk, and his pals make short work of the luggage.

After a vicious flurry of stabbings and gunshots, to which Henry seems completely unfazed, we get the first of many of the film’s iconic flourishes. Trumpets kick into Tony Bennett’s “Rags to Riches”, the screen freezes on Henry’s red-soaked face, and he starts telling us his story.

TILT UP and FREEZE ON HENRY'S face slamming the trunk shut.

HENRY (V.O.)

As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.

MAIN TITLE:

GOOD FELLAS

UNFREEZE and

DISSOLVE TO:

HENRY - AS A CHILD

So begins the introduction to Henry Hill. It’s a familiar rags-to-riches montage, heavy on expositional voiceover with plenty of romantic period-era songs. Henry’s an outsider, always looking into the world of his Brooklyn crime-riddled neighbourhood with the same excitement and fascination as the audience.

From this point, the entire narrative unfolds more or less chronologically. For the next two-and-a-half hours, we’re strapped to Henry’s perspective as he’s gradually allowed into a world that allows him to be “somebody in a neighbourhood full of nobodies”. What allures Henry to the life is its juxtaposition to his domestic upbringing: a world of domineering and abusive parents, rules, and subjugation.

As a child, Henry is a sympathetic character. But we’re continually reminded of his cold-blooded expression in the opening scene, as he slammed the trunk on a freshly-killed victim, via the voice-over of the adult Henry that permeates the childhood sequences.

On the sidewalk WE SEE the TWO HOODS who just got out of the car hug and playfully shove TUDDY VARIO, the sloppily-dressed, solidly-built HOOD who runs the cabstand.

HENRY (V.O.)

They weren't like anyone else. They did whatever they wanted. They'd double-park in front of the hydrant and nobody ever gave them a ticket. In the summer when they played cards all night, nobody ever called the cops.

Henry’s primary motivation is social inclusion and access to privilege. But it’s the inclusion of an outsider to a culture outside the rules of normal society. And it’s an access to privilege that is based on corruption, violence and contempt for the ordinary person. I don’t think these are framed as simple ethical choices. Scorsese shows a precarious and ambivalent relationship between inclusion and exclusion, between glamour and depravity.

Many scenes revolve around lavish dinners or insider’s only card games. These are dimly-lit and inviting. It’s a boys-night-out with thousand dollar suits and an unlimited bar tab. But the camaraderie is always on a knife’s edge. For every time that Joe Pesci’s volatile Tommy DeVito can forgive an off-hand comment, there’s the other time that he’ll get pissed-off during a card game and shoot the waiter dead.

Gradually, we watch Henry Hill attain the status and access he longed for as a child. Sure, there are limits: he’ll never be a “made guy” because his family lineage can’t be traced back to Sicily, and his rise in the ranks is largely thanks to riding the coat-tails of Robert De Niro’s ruthless James Conway. But the audience can vicariously share in his ascent.

Of course, it all falls apart. How else could we have someone telling this ostensibly factual story without inevitable betrayal, exile and law enforcement involvement? And how else could we secretly enjoy their transgressive behaviour without the lurking sense that somehow, eventually, these lovable psychopaths will get their comeuppance?

Henry’s need mirrors our very human need to belong. And Goodfellas provides the catharsis of that need with the extra thrill of looking from behind a screen into a closed-off world of criminal enterprise and grandiose entitlement.

Compare the opening of Casino. After some minimal producer title cards, we are greeted with the sight of a closed glass entrance. The doors open outwards and Robert De Niro exits to a car park, with the camera following him in a single-take as his voice-over track begins:

EXT. RESTAURANT PARKING LOT, LAS VEGAS, 1983 - DAY

SAM 'ACE' ROTHSTEIN, a tall, lean, immaculately dressed man approaches his car, opens the door, and gets inside to turn on the ignition.

ACE (V.O.)

When you love someone, you've gotta trust them. There's no other way. You've got to give them the key to everything that's yours. Otherwise, what's the point?

ACE (V.O.)

And, for a while... I believed that's the kind of love I had.

Then — bang! The car explodes.

It’s classic in media res, but this time, we have even less context than the character on screen. The fireball is just as surprising to us as it is to this nameless character. Before we’re able to take in the visual and its import, the grand scale chorus of “Wir setzen uns mit Tränen nieder” from J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion blasts us into Casino’s hallucinogenic title sequence.

Directed by Elaine and Saul Bass, this sequence shows our nameless protagonist falling through flames, which eventually dissolve into casino lights.

Already, it feels dislodging and disorienting. What’s going on? With almost three hours still to go, we’re sure we’ll find out. But hasn’t the ending been spoiled? We already know the outcome, so surely the dramatic tension has been ruined.

There are many ways to tell a story. Not an infinite number, but a clustered patterning of tension and release, rise and fall, redemption and damnation.

Goodfellas tells us its story in a familiar rhythm, the bumping of the tarmac seams. Casino attempts another, trickier road. The key triggers the switch, the engine turns and everything explodes. The die is cast.

The Sense of an Ending

When we meet Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) in Goodfella’s opening, he’s an accomplice to a murder that doesn’t faze him. He’s always wanted this life. He watched the neighbourhood gangsters flagrantly breaking rules and getting away with it, squeezing the common man for their piece of the pie, and he saw heroes. Before long, he’s on his way: part of an amoral fraternity with access to privilege and camaraderie.

The audience vicariously shares in Henry’s ascent. The drugs, the money, the ersatz glamour of backdoor access to the Copacabana nightclub complete with your own front-row table to the show. But in a world with few rules and everybody out for themselves, it’s only a matter of time before the wheels come off.

The 10-minute sequence in the third act (titled above) is an extended paranoid freak-out as we race alongside a coked-out Henry on a series of criminal and domestic chores. All the while, he’s under helicopter surveillance and his home phone is being wire-tapped. It’s a bravura sequence of breakneck editing, classic needle drops, and sustained stimulant-driven tension.

While preparing the veal, he ducks outside the front door to scan for helicopters and the audio track slips in a vaguely hallucinogenic piece of dialogue heard off-screen.

“Who’s been carving their initials in the tomatoes?”

It’s like a stress dream. With multiple plates spinning, he’s unable to convince his recalcitrant babysitter and drug mule Lois (Judy Wicks in the original script, referred to as Lois in the movie) from doing her one simple job: don’t talk on the home phone.

WE SEE JUDY WICKS take out an airline ticket.

HENRY (V.O.)

So, what does she do after she hangs up with me? After everything I had told her? After all her yeah, yeah, yeah, bullshit? She picks up the phone and calls from the house. Now, if anybody was listening, they'd know everything.

So they do. The sequence abruptly ends with Henry, in his car, being held at gunpoint by law enforcement agents. The engine stops. It’s almost a relief to the viewer.

The real-life Henry Hill died peacefully in 2012 from complications due to heart disease. He was a free man. The final scene of Goodfellas shows him living a quiet domestic life in FBI witness protection. He leaves his front door to pick up the newspaper, and while looking directly down the camera at the audience, he laments:

HENRY (V.O.)

I'm an average nobody. I get to live the rest of my life like a schnook. I have to wait around like anyone else. You can't even get decent food. Right after I got here I ordered some spaghetti with marinara sauce and I got egg noodles and ketchup.

And that’s that. Henry’s story, as far as the audience is concerned, is finished. He hasn’t learned anything. The moral lesson is subtle, implied, cautionary. As with Casino and The Wolf of Wall Street, Scorsese turns the camera around to the audience as if to say, “Show’s over folks, you’ve had your fun.” Henry Hill’s comeuppance is a life in material purgatory. If he has a conscience at all, we’re not privy to its anguish. Instead of counting his lucky stars, he’s pouting at his entrée.

Casino begins its story with the ending. A man gets in his car, turns the key, and explodes. By the mid-90s, this starting gimmick was already on its way to legendary meme status: the record scratch, freeze frame, and voice-over of the character saying, “Yup, that’s me. You’re probably wondering how I got here.” After the grandiose opening credits sequence, we’re quick to learn how.

INT. TANGIERS CASINO FLOOR - NIGHT

Vignette of ACE through rippling flames, we move in on ACE ROTHSTEIN overseeing the casino. He lights a cigarette.

ACE (V.O.)

Before I ever ran a casino or got myself blown up, Ace Rothstein was a hell of a handicapper, I can tell you that.

Ace starts at the top, literally and figuratively, cloaked in silhouette then turning towards a camera facing up towards him.

We learn nothing about his upbringing or his eventual introduction to working for the Mafia. But he has a gift for sports gambling. We’re told that when he places a bet, he moves the odds for the entire bookmaking industry. He’s cold, unknowable, and more than a little obsessive. And for all we know, he’s already dead.

Show-and-tell: why not both?

Casino breaks the age-old wisdom of “show, don’t tell” when it comes to storytelling. There are over 400 lines of expositional voice-over lines in the final script. This is based on a true story. The intricacies of the Mob-ruled Vegas strip of the 1970s involve complicated machinations of corrupt Teamsters unions and dark money. It’s a lot to pack in. Voice-over helps. It’s partly due to necessity.

ACE (V.O.)

I was given one of the biggest casinos in Las Vegas to run, the Tangiers...

INT. SAN MARINO ITALIAN GROCERY/BACK ROOM, KANSAS CITY - NIGHT

Vignette of MOB BOSSES sitting at a table surrounded by food and wine like the gods of Olympus.

And partly, it’s because Casino is not a subtle movie. It’s not going for ambiguity. The script describes the mob bosses “like the gods of Olympus” and the camera frames them in classic Last Supper tableau while the strains of Bach’s “Wir setzen uns mit Tränen nieder” continue to play over the soundtrack. This is Scorsese in full operatic modality. Henry Hill might have looked enviously into the life, while Ace Rothstein is blessed by the Gods; already encapsulated into its Faustian dilemma.

ACE (V.O.)

...by the only kind of guys that can actually get you that kind of money: sixty-two million, seven-hundred thousand dollars. I don't know all the details.

Your mileage may vary, but I never tire of the constant voice-over dialogue. It’s good writing voiced by some all-timers: Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci (with a few exceptions) tell us the tale and it’s fairly playful. Characters finish each other’s sentences in voice-over. There’s some irony in having omniscient narration of events that none of the characters could have known or suspected. (This is played to devastating effect when, in the third act, Nicky’s non-diagetic voice-over is interrupted with a scream of pain as he’s cracked over the head by a baseball bat. After the death of his character, we don’t hear from him again.)

Ace and Nicky engage in a battle of wills throughout Casino as Ace struggles to assert his dominance and control over his ‘Paradise on Earth’, the Tangiers casino, while his domestic life unravels. Ultimately, we know it ends in tragedy because the gods of Olympus will undoubtedly have the final say. We saw the initial scene. Ace explodes in his car, deus ex machina style.

Ace and Nicky are the Greek chorus to the proceedings. While both characters will reveal Shakespearean character flaws that describe their downward arc, Casino is more Seven Against Thebes by Aeschylus than anything by Shakespeare.

Conclusion

Start talking about The American Dream and I’ll likely nod off within 15 seconds. More like The American Nightmare, amirite? It’s a dusty old trope that ascended to literary prominence in books like “The Great Gatsby” (snore) and plays like “The Death of a Salesman”. You can even read it in Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” if you squint a little.

The trope of The American Dream may have held relevance in post-War America to refer to a swathe of broad political, economic and social trends. Today, it’s a lazy shorthand that critics use as a crutch.

Now excuse me while I do exactly that.

Labour, Capital and The Divine Source

Scorsese’s crooks are liars, cheats and sociopaths. They’re parasites who operate outside the law to extract value. In Goodfellas, this is performed within the labour market. Mobsters hijack trucks laden with consumer goods and stage airport heists by tipping off working stiffs paid minimum wage.

Casino and its Kansas City mobster cartel don’t need to work as hard. They’ve plugged into the divine source: the “morality car wash” of Vegas with its semi-legitimate business ties to the Teamsters. They don’t need to shake down local groceries for protection rackets. Their marks are already willingly opening their wallets. All they need to do is skim off the top.

ACE (V.O.)

At that time, Vegas was a place where millions of suckers flew in every year on their own nickel, and left behind about a billion dollars. But at night, you couldn't see the desert that surrounds Las Vegas…

It’s like manna from Heaven. A man-made Eden for the twentieth century. And unlike Goodfellas, there’s no need to fence your stolen truckload of muskrat fur coats. The physical labour of truck-jacking and plane heists has become mechanized and streamlined.

The Wolf of Wall Street is the ne plus ultra of the criminal American Dream. Theft is no longer a physical process or a mechanized one: it’s not even controlled by the Mafia. Jordan Belfort is a stockbroker who lied for a living and made millions of dollars doing so: his divine source was the telephone. It’s even tackier than Vegas: the drab walls of The Wolf of Wall Street’s call centres and the flat framing of the cinematography don’t have the dimly-lit nostalgic romance of Scorsese’s earlier gangster flicks. There’s not even the thrilling danger of violence. Worst case, you’ll get arrested, then released. The gig’s up: crime is automated and financialized. Now go check your NFT collection and your Bitcoin wallet.

Casino laments this banal new reality in the very final stretch. After all the legal proceedings, the murderous reprisals of the gods of Olympus and the banal fate of Sam Rothstein returning to his sportsbook operation, Vegas gets rebranded. Now, it’s Disneyland. The old world with its pyramids and palaces tumble down with fire and brimstone and Big Corporate paves over the new one.

ACE (V.O.)

After the Teamsters got knocked out of the box, the corporations tore down practically every one of the old casinos. And where did the money come from to rebuild the pyramids? Junk bonds.

And those junk bonds are exactly how Jordan Belfort made his millions. By the way, just like Henry Hill and Ace Rothstein, Belfort didn’t get whacked by the Mob. As of time of writing, he’s not even in jail. Check back in a few years and let’s see how Sam Bankman-Fried’s doing. Maybe Netflix has the rights to his life story.

Final Thoughts: Lucky Ace Rothstein

Oh yeah, I forgot: remember Ace’s car explosion at the start of Casino? He didn’t die.

ACE (V.O.)

No matter what the Feds or the papers might have said about my car bombing... it was amateur night, and you could tell. Whoever it was, they put the dynamite under the passenger side. But what they didn't know, what nobody outside the factory knew, was that that model car was made with a metal plate under the driver's seat. It's the only thing that saved my life.

Again, we have that cheeky omniscient narration. Ace may claim “it was amateur night, and you could tell.” But he couldn’t possibly have known about the metal plate under the driver’s seat. Not that I would put it past him: Ace is a stone-cold mathematician, always factoring in variables that make him the best odds-maker in the business.

His obsession with control and fastidious attention to detail make for some morbidly humorous anecdotes. He gets extremely frustrated when the slots machine floorman doesn’t twig to an obvious scam. He tells the Tangiers’ chef de partie that he wants an equal amount of blueberries in each muffin served.

“Do you know how long that’s going to take?”

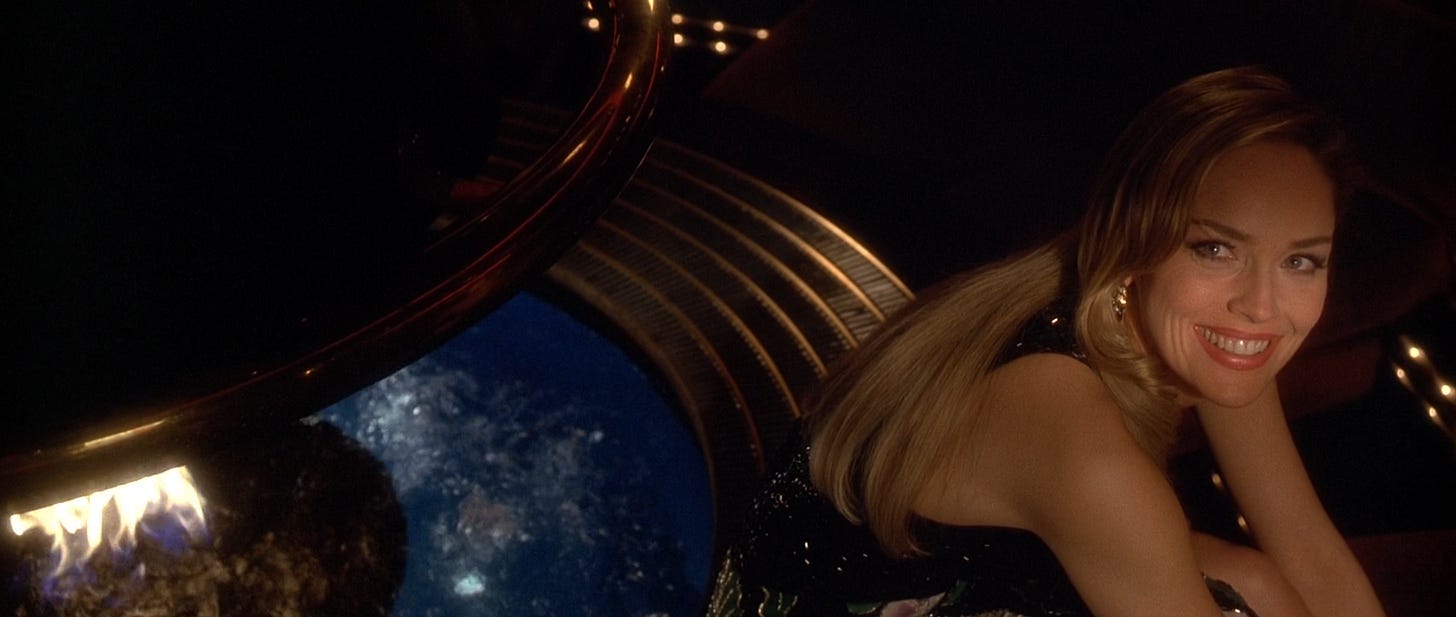

All of which makes his decision to blindly trust his heart and marry Ginger his Shakespearean flaw. Ginger is Ace’s shadow opposite: vivacious, impulsive, volatile. As well as her physical beauty, this attracts Ace.

When he first spots Ginger making a scene by throwing a high-roller’s chips to the wind, he’s both amused and intrigued. He already knows she’s the one for him.

The scene where Ace proposes to Ginger is almost heart-breaking.

ACE (V.O.)

Within no time, everything was set in place. We got rid of the freelance scamsters. The per was way up. The gods were happy, or as happy as the gods can ever be. And I, I decided to complicate my life. For a guy who likes sure things, I was about to bet the rest of my life on a real longshot.

She tries to let him down gently, saying, “Sam, you’ve got the wrong girl. Do you know a lot of happily married couples? Because I don’t.” Sam bashfully brushes ash off his smoking jacket while looking down.

Eventually, he persuades her the only way he knows how: by promising enough money to set her up for life. The only thing he asks for is trust. But neither character truly trusts one another. For the remaining two-and-a-half hours, we watch their doomed union slowly unravel into bitter recusal, animosity and estrangement.

Ginger’s character and Stone’s performance is legendary in Casino. I could easily spend another 1,000 words writing about it. But suffice it to say, she is not Ace’s undoing. And neither, in the end, is Nicky. The end of Casino is written in the first scene. If you re-watch it (and I hope you do) look for those gods of Olympus right from the very start.

Casino knows what it’s doing. It’s not a pale imitation of Goodfellas more than an extrapolation. For all its excess, for all its indulgence, I still love it. A Greek tragedy, an opera, a requiem. And best of all: a helluva entertaining movie.

Thème de Camille - Georges Delerue

Thanks for reading!